Five years ago, on the 21st of March 2014, Vladimir Putin signed the federal constitutional law on the admission of Crimea to the Russian Federation. Several days earlier, the peninsula had brought down the curtain on the Ukrainian past in the referendum. Later, a now famous slogan appeared on the streets of Simferopol: "What's next? Come hell or high water - we are home now!"

However, this did not affect everyone. The admission to Russia has resulted in the closure of the substitution treatment programme, catching many off guard. It has become a real nightmare for former "drug addicts", or, more precisely, consumers of psychoactive drugs. At least for those who had been receiving methadone treatment for several years by then.

Haven of Refuge

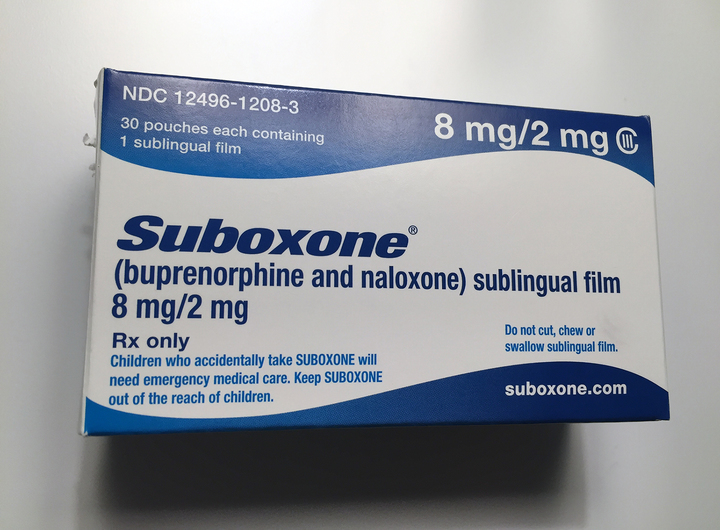

Opioid substitution therapy (OST) is a method to treat opioid dependence when a patient who is not ready to give up on drugs completely is prescribed a replacement medication. It is chemically similar to morphine and can help to overcome cold turkey without causing euphoric effects. The most commonly used are methadone and buprenorphine.

This therapy entails a total abstinence from "street drug use". With methadone programmes, if the patient takes more than prescribed, they will get an overdose. As for buprenorphine, the drug will simply have no effect. Besides, the treatment implies socialisation, health monitoring and appropriate treatment in case HIV or tuberculosis are detected.

Both antiretroviral and other anti-infection drugs are provided in the same office as the substitute. You come for methadone and also take other medicines prescribed by the doctor.

Substitution therapy has proved to be one of the most efficient tools for harm reduction of drug addiction in all countries where it is available. Moreover, it is a unique method of HIV preventive treatment that allows social services to work with the most difficult and least accessible groups.

The therapy has existed in Ukraine since 2003, and since 2008, the programme has been available in almost all regions of the country. But the first tests and approbation of the technology were conducted right here, in Crimea.

Death Epidemic

"After medications had run out, it was a real hell for a week," reveals Pavel, our interlocutor, whose full name we cannot disclose for safety reasons, as well as full names of other heroes in this article.

Substitution therapy is prohibited in Russia, and the spread of methadone or buprenorphine is similar to drug traffic.

Immediately after the admission of the peninsula, new authorities forbade doctors from prescribing these substances, suggesting that patients either move to mainland Ukraine or undergo detox and treatment in Russian clinics.

As a result, dozens of former substitution therapy patients died according to Michel Kazatchkine, United Nations Special Envoy for HIV/AIDS in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Russia, in turn, protests that only seven OST clients died in the peninsula in the period from March to the end of December 2014. But reality seems to be much more frightening.

"I can say with certainty that if at least a couple of hundreds out of 826 people who participated in the programme have survived, that's already something to be happy about. It was a horrible time," says our other interlocutor from Crimea (let's call her Marina), a long-time drug user and an OST patient.

"In Kerch, people jumped from apartment buildings, unable to handle withdrawal symptoms," Pavel illustrates her words. He is a native Crimean, who is a drug user and a participant of the methadone programme too. But he left the peninsula soon after the events of the "Russian Spring".

"Getting off methadone is a very long-term process. I could barely describe the state you experience in case of cravings. Everything is getting out of control," tells the woman. She adds that after access to the medication had been blocked, many people she knew switched over to street drugs and eventually "failed to handle the situation". Some died from overdose, some turned into alcoholics, some hanged themselves. In Simferopol, immediately after the therapy was banned, the Russian Federal Drug Control Service conducted a series of raids, that stopped street drug trafficking for a while.

However, there were no portents at first. "In the last days of March, we all were excited, of course, that we would join Russia. We didn't know what the conditions would be like," recalls Pavel.

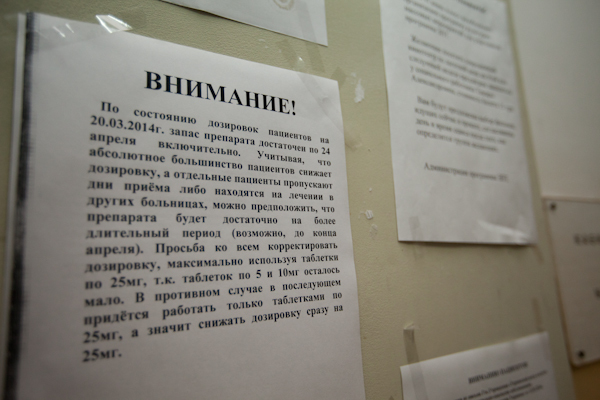

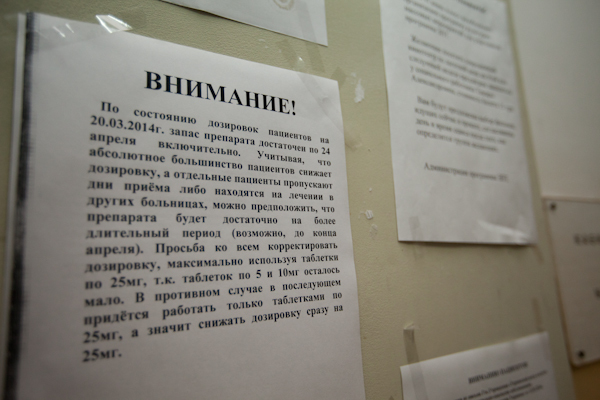

And if at first, after the "historic victory", the so-called fighters for the Russian world did not even think about the substitution programme, a month later clouds began to pile up over methadone users.

"We were kept in suspense: they told us that the Ministry of Health had agreed to continue the programme till the end of summer. But already in the beginning of May, they suddenly announced that we had to reduce the dosage ourselves. And on the 20th of May, they just told us that it was the last day," explains Marina.

Golden Prescription

According to many people we have talked to, if the Russian security forces had not confiscated and disposed of the pills delivered to the region when it was a part of Ukraine, there would have been enough medicine until the end of 2014. But the police logic prevailed over the medical one.

"Those who had not been admitted to hospitals due to a shortage of places to undergo detoxification, were given one pack of tramadol and one pack of phenazepam in order to kick the habit. But if a person had a dosage of 150 mg of methadone, such an amount wouldn't even relieve the withdrawal," says Pavel.

Tramadol is an opioid painkiller. It belongs to partial agonists of opioid receptors, but it is many times weaker than even heroin. Phenazepam is a benzodiazepine drug, a sedative, which is prescribed for neurotic disorders, spasms, and as a sleeping pill.

Pavel vividly describes the methadone withdrawal state and sighs: "How could a pack of phenazepam help here?"

"By the way, while tramadol was brought to Simferopol right away, Kerch got it when people had already started to slash their wrists. Russian officials just didn't care," he continues.

Jogging in Place

"There was no tramadol in Yalta at all, the doctor just stole all the prescriptions, put them into the boot and left. As a result, no one got anything," Marina adds to his story. "For a while, it was possible to bargain to get buprenorphine in the Simferopol clinic. But they pulled the plug on it soon after. If I am not mistaken, a criminal case was initiated against the doctor who helped us."

According to the woman, she herself was saved exactly by prescriptions for the analgesic obtained at a pharmacy in advance, as well as her child.

"In Kerch, people jumped from apartment buildings, unable to handle withdrawal symptoms"

Many patients on OST had children. That is exactly the idea of the substitution therapy: people who once lived from dose to dose get rid of the need to buy drugs and go back to their normal life rather quickly. "When there is no buzz, cold turkey, or need to go out into the street and deal with criminals, the former drug user finds a job quite soon, settles down, even has children. We even had guys who worked at a bank. And suddenly they lost everything," explains Marina. "Nobody expected that the programme could be cancelled one day."

Former recipients of the therapy tell an illustrative story: one day a deputy of the Russian Minister of Health came to the "site" (that is what OST offices are called), and a woman rushed to her with a plea: "I used to be on methadone and gave birth to a child. Everything is fine, I have a family. But how am I going to live now?" "We wouldn't even let you give birth to a child," the official answered relentlessly. "It is not accepted to talk this way in Ukraine. Everyone was shocked, but at that time we didn't understand what Russia is like," Pavel admits now.

After going through some painful experiences with new authorities and having found no other option, he decided to escape.

"When I was in the hospital again and entered an office, there was a doctor I knew, who showed me a pre-typed text on his phone screen: "If you want to leave for Kiev, we'll help"". The registration for evacuation had already been finished by then. But Pavel managed to get "involved" into the shuttle at the last moment, and, together with many former drug users, move to the territory controlled by the old authorities.

on the topic

Treatment

Бупренорфин животворящий. Как Франция остановила наркоэпидемию

But it did not last long: "I found a good job in Kiev, I even rented a flat, but then my father fell ill. He had cancer. So I had to come back."

Over the years, since those events, a whole generation of civil servants has changed in the peninsula: high-profile resignations alternated with public scandals, administrative disputes, redistribution of property. Plus, there were the Ukrainian blockade, blackouts, price rises, and border conflicts. Finally, there is the war in Donbass, which has almost squeezed the region out from the Russian newspapers.

By the way, the OST is now illegal there too. In October, AIDS.CENTER wrote about the human rights activist Andrey Yarovoy, who was arrested by the Ministry of State Security of the Luhansk People's Republic for storing buprenorphine. Andrey helped former recipients of substitution therapy in the unrecognised state. The new authorities copying the Russian drug policy charged him with smuggling of prohibited substances under Part 3 of Art. 282 of the Criminal Code of the LPR.

Mass media made almost no mention of Crimean patients during that time, except for rare publications by the BBC Russian Service and a couple of pieces prepared by the Radio Liberty journalists.

In Search of Healing

In Russia itself, disputes about the substitution therapy have been in progress for years, even though the official position of the Ministry of Health on OST, published in 2016, seems to set the record straight (when asked for a comment, officials of the specialised department in Moscow refer to this document in particular).

According to the Strategy of the Russian Federation National Anti-Drug Policy until 2020, both the methadone programme and the buprenorphine one are prohibited in the country.

Moreover, "the main measure to improve the effectiveness and development of drug treatment is to prevent the use of substitution methods to combat drug addiction in the Russian Federation". The document does not explain, how exactly the ban on OST increases the effectiveness of other medical approaches.

On the 6th of August 2018, even the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs criticised OST, which is widely used in the West and recommended by the world's leading experts. Back then, Oleg Syromolotov, the Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, shared the negative opinion about the therapy, which had been repeatedly expressed by the Minister of Health Veronika Skvortsova. He claimed that the controlled distribution of buprenorphine or methadone undermines the "effective multi-level treatment and rehabilitation process for drug addicts with their total abstinence from drugs".

"It is not accepted to talk this way in Ukraine. Everyone was shocked, but at that time we didn't understand, what Russia is like"

"But substitution therapy is not the antithesis of rehabilitation. They are two different stages, they do neither exclude nor interfere with each other," Lev Levinson, an expert of the Human Rights Institute and head of the New Drug Policy programme, argues with the position of Moscow and federal medical officials.

And leading medical specialists generally agree with him: "OST is not a panacea, but a motivational mechanism that works only when effectively integrated into the treatment context. Substitution therapy as such does not cure, but the environment where a person finds themselves does. It changes their modus vivendi. A person starts taking drugs when they experience mental and moral vacuum, when they do not see the point in being sober. A drug is a way to adapt to the challenges and difficulties people face," says Oleg Zykov, a Candidate of Medical Sciences (PhD) and a recognised narcologist.

According to him, substitution therapy should be seen as a part of the whole rehabilitation context, just like the rehabilitation should be considered in relation to the resocialisation of the drug user.

But together with other measures that motivate the patient to lead a socially acceptable lifestyle, OST can be very effective. "One cannot be forced or somehow convinced to recover. Only search and rethinking of the meaning of life can encourage the patient to go for rehabilitation," the doctor emphasises.

"There are statistics: no matter how well the processes of detoxification and rehabilitation are arranged, 80% of patients still fail and go back to drugs," says Maxim Malyshev, coordinator of the Andrey Rylkov Foundation, which provides social support to consumers. He urges that OST should be considered as one of the legitimate ways to solve the problem. At least in cases where support groups or traditional rehabilitation in a clinic did not help.

'Opponents of substitution treatment often say "we do not treat addiction this way". Yes, substitution therapy is not a treatment of addiction in itself, it is a treatment of symptoms,' insists Malyshev. "But when other methods did not work, why can't we give people a chance to live without hitting the backstreets in search of drug stashes or paying money to drug dealers. Why can't we give them a chance not to get HIV?" he asks. Well, it is a rhetorical question.

However, the Ukrainian programme has had its own drawbacks. For example, Marina claims she bribed her way in. To be enrolled on the list, the woman had to "grease a palm" with 100 dollars. The same problems with OST could have been in our country, if it were legal here. Nevertheless, this technology has made it possible for thousands of people in Ukraine to get back into society. And has not done the same for millions of Russian citizens.

"Russian position on substitution therapy is outdated," Levinson sums up. 'There is some inertia reinforced by a snobbish political motto, which is trendy now: "We have our own way". But the ban on OST it not exactly the way of Russia. It originates from the Soviet Union and the Permanent Committee for Drug Control, whose chairman, Dr. Eduard Babayan, actively opposed it. But over thirty years have passed since then. Today substitution therapy is recognised by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and is commonly used even in those countries where drug policies are even more strict than in Russia, for example, in Iran and China.'

A Modicum of Optimism

Interestingly enough, in September 2018, the First Deputy Director of the Federal Penitentiary Service Anatoly Rudy surprisingly expressed support for OST at a special meeting of the Human Rights Council under the President of the Russian Federation. He stated that substitution therapy for drug addicts in Russia could decrease the number of crimes committed by them, thus reducing the number of prisoners, who serve their sentences under articles on drug dealing and possession.

"One cannot be forced or somehow convinced to recover. Only search and rethinking of the meaning of life can encourage the patient to go for rehabilitation"

His immediate superior, who had providently gone on a vacation, could not disavow his colleague's statement. And even though it is a matter for conjecture whether his departure overlapped the Council's meeting deliberately or not, obviously, there is a difference of opinions on this issue, albeit unspoken, even in the top circles of Russia.

It is worth noting that the Crimean ban story did not end so badly for some people. Having been deprived of methadone, our third interlocutor from Crimea, Valery, got into a Rostov rehabilitation clinic, established by one of the Protestant denominations.

He had been using drugs for 15 years, spent several years on OST. And after the admission of the Crimea to Russia, he switched over to the street "high". Doctors and detox did not help: "Drug addicts could buy anything in the drug clinic in Simferopol, you could get any drugs there. A drug addict would find a loophole everywhere," and here it worked. He says that God helped him.

But anyway, now Marina and Pavel do not use drugs either, though they have pulled through without going to church. But they still share all the difficulties and stigmas with their former fellow sufferers: "Nowadays, few drug users in Crimea have a job, and it’s difficult for me to find something too. According to the Russian Law, you have to provide a certificate from a drug therapist, when applying for a job," explains Pavel.

"I'd love to come back to Kiev, if it weren't for my mother who stayed here alone after my father's death", he says. "There, in Ukraine, we are still treated better than in Russia." And he demonstrates this difference with a story: 'When the manager of the hostel where I lived for some time, found out I was going through the methadone programme, she called the police. When they arrived, they suggested that I sue the manager for insult: "He is not a drug user, he's on treatment. This is permitted by the state."' In his Crimean homeland, Pavel probably should not expect to see such "tolerance" very soon. Unless, of course, the rebellious peninsula does not decide to get back under the "Kiev wing". However, optimistically counting on that would not only be a naive, but also quite a dangerous thing to do.