Ilya and Evgeniy are a gay couple from Belarus. They have been living together for several years, and call themselves an “interesting couple”, because they have a discordant relationship. Not long ago, the condom broke while they were having sex. They decided to undergo post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP). It seemed simple: you need to start taking pills within 72 hours after the risk of infection occurs. It seemed especially simple since the steps needed to take are well known: you see a doctor, explain the situation, get the pills, take a month’s course, and forget about the problem. But due to the peculiarities of local legislation, it is much more difficult to get help than it seems at first glance. AIDS.CENTER found out what Belarusian discordant couples have to deal with, and what the possible ways out of the current situation are.

Rat on your friend and get the pills

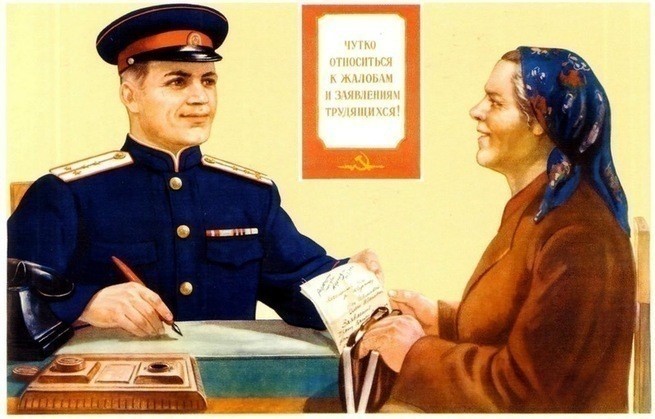

“When our condom tore, we talked to our friends, and went to the infectious diseases hospital in Minsk on Kropotkin Street to get PEP,” Ilya recalls. The doctor listened to him “with a disgruntled look on her face”, and asked him to reveal his partner’s name. She explained that the man should be registered, and that in these cases, the medical officer "must report to law enforcement authorities".

The man asked whether that law had not been repealed yet, but he was told that the law was in effect, and that the partner would be held criminally liable. Of course, the man refused to turn Evgeniy in, but the doctor kept insisting: “How can I know? What if you are slandering someone? What if you are going to sell the medicine that I’ll give you?" So he did not get the pills.

The Criminal Code of Belarus does contain Article 157 (Human Immunodeficiency Virus Transmission), which says that if one person deliberately puts another in danger of being infected with HIV, they can be sentenced to prison time. Notably, the article provides for criminal liability, even if the victim has not made any claims against the defendant. And legal proceedings can be initiated by infectious disease specialists. By the way, Belarus and Russia are the leaders in the criminal prosecution of HIV-positive people. For example, in 2017, 130 criminal cases were initiated under Article 157 of the Belarusian Criminal Code.

However, the legislation in the republic may be eased in the nearest future. The amendment to decriminalise transmission of the disease was adopted on December 19, 2018. According to it, HIV-positive people will no longer be prosecuted “for putting their partners under the threat of HIV transmission and HIV infection”, if they notify them in advance about their state. The bill has been submitted to the Council of the Republic, and to the president for approval.

“There are still a dozen of prohibitions for people with HIV-positive status in the legislation of Belarus,” says Irina Statkevich, chairman of the local HIV-service organisation “Positive Movement”. 'Positive changes to the standard "HIV-positive children are prohibited from doing sports" were made in 2018. It is noteworthy that HIV-positive children initiated the changes in the regulations themselves. They participated in a meeting at the Ministry of Health.”

Moreover, HIV-positive people were forbidden to adopt children before. This article has been revised, however, there are still some nuances in its application.

Who is responsible for one's health?

Ilya is convinced that his health is his own responsibility. He used to work as an HIV consultant himself, and conducted rapid tests, so he knew that there were only three days to do PEP after unprotected intercourse.

“In my opinion, the doctor was very unprofessional,” he complains. “There was a reason for concern because at that time my boyfriend and I didn't know his exact viral load.”

“Just as in many other countries, there is no document in Belarus that clearly defines the indications of post-exposure prophylaxis, and this is due to some objective difficulties,” says infectious disease specialist Nikolai Goloborudko.

According to him, PEP is provided in case of occupational exposure, for example, if a nurse gets pricked with a needle she used to take blood from an HIV-positive patient. It is also provided in some everyday situations. For example, if a child finds a syringe in a sandbox, and pricks themselves with it, or in case of certain sexual incidents such as rape.

Statkevich agrees that there is currently no regulations system for distribution of such pills. “So there hardly exists a formal requirement to name your partner,” she says, assuming that the doctor could ask for the data of the partner to evaluate the risks. “The doctor could look up the viral load information in the partner’s registration card, and thus understand if there really is an emergency.”

Ultimately, Ilya received the post-exposure prophylaxis, but not from the doctors who were supposed to provide it. His acquaintances from Russia helped him, and promptly provided the medication.

He is going to be tested soon, and if the results are positive, he wants to see the same doctor: “Because it was her who jeopardised my health and my life. I believe, such requirements of a doctor violate the law of medical confidentiality, and disclosing a person’s HIV status can be a criminal offence. After all, there are people who would use this information with malintent.

How can the situation be changed?

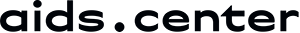

According to Statkevich, the example of Ilya is a good demonstration of how HIV prevention is related to legislative regulations, particularly to Article 157. “This topic has been widely debated lately, there are real cases of imprisonment. And many people seek to keep the secret at any cost, so as not to harm their HIV-positive partner,” she adds.

The public organisation advocates that criminalisation of HIV transmission should be reduced, offering several points. First of all, it is necessary to reclassify cases under article 157 from a public charge to a private one. It means that they will not be initiated by representatives of the Ministry of Internal Affairs or prosecutor’s offices, but by a person affected by the crime. Besides, the cases can be closed upon reconciliation of the parties.

Secondly, the possibility of blackmailing by an HIV-negative partner must be excluded. To do this, community activists offer either to obtain the "informed consent to have sex with an HIV-positive partner", for example, from an infectious diseases specialist or, more realistically, to supplement the criminalisation article with the phrase “in case of failure to take infection-preventive measures (refusal to take antiretroviral therapy or use a condom)”.

Thirdly, to define the terms of the Criminal Code article more clearly, such as “deliberately”, and others. Because the wording ambiguity allows to interpret them unnecessarily broadly.

“Just like in many other countries, there is no document in Belarus that clearly defines the indications of post-exposure prophylaxis"

“Drug prevention treatment after unprotected sex is sometimes needed, but it should not become a substitute for concern about the safety of one’s sexual behaviour and replace the use of condoms,” says Goloborudko.

The doctor adds that there is another effective preventive method for people with an increased risk of infection, for example, for men who have sex with men, and for sex workers. It is known as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

However, there is a problem with the access to pills for both PrEP, and for PEP. Procurement of antiretroviral drugs in Belarus is centralised, and funded by the state budget. Pharmacies simply do not get them, that is why it is impossible to buy them yourself, at least legally. Which means that, due to the stigma, the fear of opening up even to doctors, and the unwillingness to turn in partners, the number of people with HIV can increase. The principle is simple: if you do not get treatment, you either get infected yourself, or you transmit the virus to another person. We can only hope - at least, there are talks - that pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis programmes will be launched in Belarus, that could be provided not only in public hospitals, but in NGOs as well.